islam and science

Islam and science addresses the relationships between the religion of Islam, its adherents' (Muslims) communities and the activities known collectively asscience. As with all other branches of human knowledge, science, from an Islamic standpoint, [is] the study of nature [as stemming from?] Tawhid, the Islamic conception of the "Oneness" of God.[1] In Islam, nature is not seen as something separate but as an integral part of a holistic outlook on God, humanity, the world and the cosmos. These links imply a sacred aspect to Muslims' pursuit of scientific knowledge, as nature itself is viewed in the Qur'an as a compilation of signs pointing to the Divine.[2] It was with this understanding that the pursuit of science, especially prior to the colonization of the Muslim world, was respected in Islamic civilizations.[3]

Theoretical physicist Jim Al-Khalili believes the modern scientific method was pioneered by Ibn Al-Haytham (known in the Western world as “Alhazen”), whose contributions he likened to those of Isaac Newton.[4] Alhazen helped shift the emphasis on abstract theorizing onto systematic and repeatable experimentation, followed by careful criticism of premises and inferences.[5]Robert Briffault, in The Making of Humanity, asserts that the very existence of science, as it is understood in the modern sense, is rooted in the scientific thought and knowledge that emerged in Islamic civilizations during this time.[6]

Muslim scientists and scholars have subsequently developed a spectrum of viewpoints on the place of scientific learning within the context of Islam, none of which are universally accepted.[7] However, most maintain the view that the acquisition of knowledge and scientific pursuit in general is not in disaccord with Islamic thought and religious belief.[1][7]

Allah Has Power Over Everything

Allah, the Creator of everything, is the sole possessor of all beings. It is Allah Who heaps up the heavy clouds, heats and brightens the Earth, varies the direction of the...

History[edit]

Classical science in the Muslim world[edit]

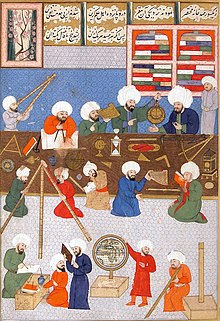

In the history of science, science in the Muslim world refers to the science developed under Islamic civilization between the 8th and 16th centuries,[10] during what is known as the Islamic Golden Age.[11] It is also known as Arabic science since the majority of texts during this period were written in Arabic, the lingua franca of Islamic civilization. Despite these terms, not all scientists during this period were Muslim orArab, as there were a number of notable non-Arab scientists (most notablyPersians), as well as some non-Muslim scientists, who contributed to scientific studies in the Muslim world.

A number of modern scholars such as Fielding H. Garrison,[12] Abdus Salam andHossein Nasr consider modern science and the scientific method to have been greatly inspired by Muslim scientists who introduced a modern empirical,experimental and quantitative approach to scientific inquiry. Some scholars, notablyDonald Routledge Hill, Ahmad Y Hassan,[13] Abdus Salam,[14] and George Saliba,[15]have referred to their achievements as a Muslim scientific revolution,[16] though this does not contradict the traditional view of the Scientific Revolution which is still supported by most scholars.[17][18][19]

It is believed that it was the empirical attitude of the Qur'an and Sunnah which inspired medieval Muslim scientists, in particular Alhazen (965-1037),[20][21] to develop the scientific method.[22][23][24] It is also known that certain advances made by medieval Muslim astronomers, geographers and mathematicians were motivated by problems presented in Islamic scripture, such as Al-Khwarizmi's (c. 780-850) development of algebra in order to solve the Islamic inheritance laws,[25] and developments in astronomy, geography, spherical geometry and spherical trigonometry in order to determine the direction of the Qibla, the times of Salah prayers, and the dates of the Islamic calendar.[26]

The increased use of dissection in Islamic medicine during the 12th and 13th centuries was influenced by the writings of theIslamic theologian, Al-Ghazali, who encouraged the study of anatomy and use of dissections as a method of gaining knowledge of God's creation.[27] In al-Bukhari's and Muslim's collection of sahih hadith it is said: "There is no disease that Allah has created, except that He also has created its treatment." (Bukhari 7-71:582). This culminated in the work of Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288), who discovered the pulmonary circulation in 1242 and used his discovery as evidence for the orthodox Islamic doctrine of bodily resurrection.[28] Ibn al-Nafis also used Islamic scripture as justification for his rejection of wine asself-medication.[29] Criticisms against alchemy and astrology were also motivated by religion, as orthodox Islamic theologians viewed the beliefs of alchemists and astrologers as being superstitious.[30]

Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209), in dealing with his conception of physics and the physical world in his Matalib, discussesIslamic cosmology, criticizes the Aristotelian notion of the Earth's centrality within the universe, and "explores the notion of the existence of a multiverse in the context of his commentary," based on the Qur'anic verse, "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds." He raises the question of whether the term "worlds" in this verse refers to "multiple worlds within this single universe or cosmos, or to many other universes or a multiverse beyond this known universe." On the basis of this verse, he argues that God has created more than "a thousand thousand worlds (alfa alfi 'awalim) beyond this world such that each one of those worlds be bigger and more massive than this world as well as having the like of what this world has."[31] Ali Kuşçu's (1403–1474) support for the Earth's rotation and his rejection of Aristotelian cosmology (which advocates a stationary Earth) was motivated by religious opposition to Aristotle by orthodox Islamic theologians, such as Al-Ghazali.[32][33]

According to many historians, science in the Muslim civilization flourished during the Middle Ages, but began declining at some time around the 14th[34] to 16th[10] centuries. At least some scholars blame this on the "rise of a clerical faction which froze this same science and withered its progress."[35] Examples of conflicts with prevailing interpretations of Islam and science - or at least the fruits of science - thereafter include the demolition of Taqi al-Din's great Istanbul observatory of Taqi al-Din in Galata, "comparable in its technical equipment and its specialist personnel with that of his celebrated contemporary, the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe." But while Brahe's observatory "opened the way to a vast new development of astronomical science," Taqi al-Din's was demolished by a squad of Janissaries, "by order of the sultan, on the recommendation of the Chief Mufti," sometime after 1577 AD.[35][36]

Arrival of modern science in the Muslim world[edit]

|

|

This article contains too many or too-lengthy quotations for an encyclopedic entry. (March 2008) |

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, modern science arrived in the Muslim world but it wasn't the science itself that affected Muslim scholars. Rather, it "was the transfer of various philosophical currents entangled with science that had a profound effect on the minds of Muslim scientists and intellectuals. Schools like Positivism and Darwinism penetrated the Muslim world and dominated its academic circles and had a noticeable impact on some Islamic theological doctrines." There were different responses to this among the Muslim scholars:[37] These reactions, in words of Professor Mehdi Golshani, were the following:

| “ |

|

” |

Decline[edit]

In the early twentieth century, ulema forbade the learning of foreign languages and dissection of human bodies in the medical school in Iran.[38]

In recent years, the lagging of the Muslim world in science is manifest in the disproportionately small amount of scientific output as measured by citations of articles published in internationally circulating science journals, annual expenditures on research and development, and numbers of research scientists and engineers.[39] Skepticism of science among some Muslims is reflected in issues such as resistance in Muslim northern Nigeria to polio inoculation, which some believe is "an imaginary thing created in the West or it is a ploy to get us to submit to this evil agenda."[40]

Islamic attitudes toward science[edit]

Whether Islamic culture has promoted or hindered scientific advancement is disputed. Islamists such as Sayyid Qutb argue that since "Islam appointed" Muslims "as representatives of God and made them responsible for learning all the sciences,"[41] science cannot but prosper in a society of true Muslims. Many "classical and modern [sources] agree that the Qur'an condones, even encourages the acquisition of science and scientific knowledge, and urges humans to reflect on the natural phenomena as signs of God's creation."[citation needed] Some scientific instruments produced in classical times in the Islamic world were inscribed with Qur'anic citations. Many Muslims agree that doing science is an act of religious merit, even a collective duty of the Muslim community.[42][page needed]

Others claim traditional interpretations of Islam are not compatible with the development of science. Author Rodney Stark argues that Islam's lag behind the West in scientific advancement after (roughly) 1500 AD was due to opposition by traditional ulema to efforts to formulate systematic explanation of natural phenomenon with "natural laws." He claims that they believed such laws were blasphemous because they limit "Allah's freedom to act" as He wishes, a principle enshired in aya 14:4: "Allah sendeth whom He will astray, and guideth whom He will," which (they believed) applied to all of creation not just humanity.[43]

Abdus Salam, who won a Nobel Prize in Physics for his electroweak theory, is among those who argue that the quest for reflecting upon and studying nature is a duty upon Muslims, stating that 750 verses of the Quran (almost one-eighth of the book) exhort believers to do so.[44]